Projects

Waypoints on my path of discovery

Systems can’t be controlled, but they can be designed and redesigned. We can’t surge forward with certainty into a world of no surprises, but we can expect surprises and learn from them and even profit from them. We can’t impose our will upon a system. We can listen to what the system tells us, and discover how its properties and our values can work together to bring forth something much better than could ever be produced by our will alone.

— Donella Meadows

Waypoints on my personal path of discovery

Restoration studies of sub-alpine ecosystems, Colorado.

Studies of latitudinal responses of species to climate change.

Partnerships with the Malpai Borderlands Group - collaborative ecosystem conservation.

.McKinney Flats - Landscape-level studies of complex interactions in arid environments.

Advising and co-leading the United Nations global grasslands program.

Two-cowboys project - Cross-continent learning networks between US ranchers and Maasai.

Adaptive management program development at MIT and teaching at Harvard and elsewhere.

Collaborative policy design - fisheries conservation in the North Atlantic.

Cross-cultural conservation exchanges in the Middle East.

Anadromous fisheries restoration on the coast of Maine.

Conservation coop development with farmers and ranchers, watershed alliance establishment.

Conservation program management in Montana, including the Network for Landscape Conservation and the Blackfoot Challenge.

Regenerative conservation projects-the Sangre de Cristo Mountain Initiative, biomass energy, and wildfire recovery and mitigation.

Developing self-sustaining conservation of Panamainan cloud forest.

I undertake projects that address crucial questions facing the environment and society. The point is not to build institutions, but to build solutions that are, in turn, communicated through my writing and outreach. Solutions I hope others will mimic, refine, and expand on.

All of these projects reflect question-driven inquiry to address a particular problem. My books synthesize the insights and solutions that stem from these experiences. What worked, what didn’t, and why. The largest and most influential of these socio-ecological “experiments” are referenced below.

Explorations Using Alternative Valuation Strategies to Preserve Intact Landscapes Chiriquí Province, Panama

One of the crucial challenges facing conservation is the scarcity of mechanisms to finance the preservation of intact landscapes. The development of a cloud forest preserve in Chiriquí Province, Panama, in a crucial corridor on the continent's spine at the junction of North and South America, serves as a model for applying alternative valuation methods. In a landscape that not only has high levels of biodiversity, but also a crucial pathway for indigenous populations to follow their traditional lifeways.

Adapting to the Pyrocene: Re-envisioning Landscapes and Communities in the Face of a Warming and Drying Climate

Since the 1990s, I've worked with communities and scientists reintroducing fire, researching the interactions of climate and fire with rural communities, and helping re-create fire-adapted landscapes to improve the diversity of ecosystems and the durability of the communities that rely on them. in recent years, many landscapes in the southwest and across the west have crossed a threshold where repeated fire is no longer just a possibility - it's a near certainty. This challenge represents threat and opportunity for landscapes and communities. Cycles of fire can destroy the social and economic fabric of landscapes or present an opportunity to rethink land management.

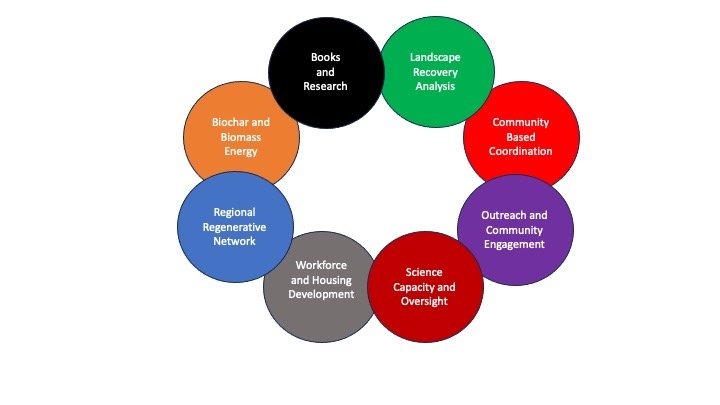

An 18th-century drawing of the Mora Valley in northern New Mexico depicts the fire-adapted landscapes we had - and could have again. Already, cycles of repeated fire in places like the Jemez Mountains are causing wholesale conversion from forests to other vegetation types. It will transform our landscapes to our collective loss - or we can actively steward them for collective gain. The choice is ours but requires higher levels of collective will and integrated planning. To that end, the Sangre de Cristo Mountain Initiative program of Regenerative Conservation Design undertaken through the for-profit Pyrocene Solutions is undertaking an eight-pronged approach to reframe the discussion and bring new tools and strategies to the table.

My work reflects a cycle of learning and leveraging action through creating networks. After decades of on-the-ground action, I stepped back and researched governance structures. As a learning organization, we began in 2019 examining sustainable ways to thin forests to reduce fire threats and increase ecological diversity while providing well-paying local jobs. This was to be done by developing biomass energy systems that provide income through carbon-negative technologies. Yet massive fires in 2022 led us to shift to landscape recovery. A lack of long-term planning and a capacity for addressing changing fire cycles led us to include partnership building, developing educational outreach, and creating a science advisory panel to oversee the action. However, we found in working with the forestry industry that a lack of workforce principally limited them, and the workforce was limited by housing. So, in partnership with Mark Lautman and the Economic Engineering group, in the spring of 2023, we began working on collective workforce and housing strategies. Additional markets and carbon-negative capacity are being developed through collaborations with a regional regenerative industry network called NM REIZE led by Terry Harris and Terry Tomlinson. The image below depicts how we are working to prototype region recovery strategies with biochar linking mountain and plains ecosystems.

At the present time all the pieces have been proven or prototyped, we are now in the processes in seeking the funding to implement early stages of the process and bringing in a range of partners to engage the community in the process. The overall goal is to show that regenerative carbon-based conservation is not only possible - but necessary! My book from Johns Hopkins University Press, Place-Based Solutions: The Power of Regenerative Thinking in the Face of Crisis (due out early 2026) articulates the path toward developing large-scale regenerative projects. Also, see SDCMI.org for more information on current place-based efforts.

Fisheries Governance and Policy

From my years of work with ranchers in the Southwest, it become apparent that one of the biggest impediments to effective conservation and other forms of societal change was poor governance.

Marine policy working with lobster and trawler fleets was a great way to experiment with, and better understand how to undertake the large-scale adaptive governance of landscapes and seascapes. The Down East Initiative focused on integrated policy development across 750,000 square miles of the Gulf of Maine with a focus on applying commons theory to cooperative governance. There are remarkable parallels between marine and terrestrial systems, and often I learned the most about terrestrial systems by watching how dynamics played out in their marine counterparts. While self-funded anadromous fish restoration efforts on the coast of Maine were early experiments in developing conservation coops that devised circular economic systems to sustain ecological and communal benefits from the environment.

Cross-Continental Conservation Exchanges and Learning Networks

Our environment and society are transforming so fast we cannot afford to keep re-inventing the wheel.

In what my Kenyan colleague David Western termed “over the horizon learning,” for years, I have collaborated to bring diverse groups from across the globe together to learn from their future through experiencing another’s present and past.

This has included the Two Cowboys Project, that over the years, brought together pastoralists from Kenya and the US to learn from each other and work with the Quebec-Labrador Foundation to organize US State Department supported conservation exchanges in the Middle East.

Collaborative Conservation and Climate Change Mitigation in Rangelands

When I finished my graduate studies in the mid-1990s, I was interested in undertaking the sorts of large-scale on-the-ground science that, then as now, are needed to address such pressing issues as climate and landscape change. However, I quickly found that much of conventional science was better adapted to helping people obtain tenure - than addressing society’s pressing challenges. At the same time, the primary funding sources, such as the National Science Foundation, were organized around disciplinary boundaries that do not map well onto the reality outside of academia.

So I left academia and formed the Arid Lands Project and, in partnership with the rancher-led Malpai Borderlands Group, crafted a collaborative community co-led science program that rivaled the scale and scope of federally funded research programs.

For over a decade, I coordinated experimental science programs in the million-acre Malpai Borderlands and developed the McKinney Flats Project, the largest replicated study on the continent that examined climate change, and interactions with plants and animals to transform arid environments.

The borderlands programs ended prematurely due to a collapse in funding following the 2007 - 2009 recession. But in my time in the borderlands, I learned invaluable lessons about the power of collaborative approaches, the need to build the social institutions to sustain science and policy, and that truly effective projects are self-funded because donor-driven approaches are intrinsically unsustainable.